Style of climb as a criterion of difficulty

Cliffs and rocks which have ceased to be mere training locations and have become a location for sport achievement have played a significant role in the developing of evaluating performance according to complexity levels, and their wider use has led to an increased focus on the method by which a climb has been achieved. The AF (All Free) style was developed in the Alps as the first recognised sport style of free climbing, where the climber uses only natural points for advancement and overcomes the route with his/her own strength. From the perspective of top climbers the rating is diminished by the fact that the climber can use any point of protection for rest. A newer, and more sporting (meaning more complex) method was implemented by Kurt Albert, who began marking all routes climbed AF without resting and in one go with a red dot at the approach. Thus the RP style (Red Point) came about. Certain climbers do not consider a route as having been climbed if it was not climbed using RP– that is, without falling and without rest. Often this requires extensive practice and preparation before such a route can be climbed by the climber. Even more highly ranked is the OS method (On Sight). OS assumes that the climber, without knowing the route, having trained or carefully examined the route using rappelling, simply comes and climbs – understandably using RP style. OS and RP are uncommonly difficult, and therefore for the average climber the RK style (Rotkreis) is more common, which allows falls and unsuccessful attempts without leaders having to retrieve their rope and begin again after every fall.

When free climbing without protection at height, this style is called free-solo. It is of course very dangerous. It is necessary to bear in mind that even the best preparation for an ascent can never completely eliminate such events as the crumbling of a handhold or other occurrences. Only an experienced and cool-headed climber can dare to climb using such a method, as the consequences in the event of a fall are fatal; the risk of death is clearly quite imminent.

Rating systems

It is entirely understandable that mountaineering like any other sport must have rules established for rating performance. Mountaineering performance has two parts: on the one hand complexity, or an expression of how exhausted we will be after a climb, and then difficulty, which designates what sort of obstacles we will need to overcome on the route. A basic tool for assessment are rating systems, of which there are many, and which were developed separately in different regions at different times. When combined with details about the style of climb, a relatively accurate picture of the complexity of the ascent itself and the capabilities of the climber can be achieved.

The process of classifying ascents itself is a very subjective matter. The degree of difficulty is proposed by the first ascentionist, and other climbers then confirm or modify this according to their own opinions. It is therefore a long-term process. Subjectivity is expressed primarily by the fact that if a climber contributing to the rating of a route is strict towards himself, he will create a so-called hard classification (a more complex ascent is rated with a lower grade); while if they overestimate their ascents, they will create a so-called soft classification (the ascent has a higher grade than it deserves).

The actual construction of a rating system can be one of two types, either a closed or an open rating system. A closed system has a maximum level of difficulty established, and if a climbed route is more complex, an older ascent route must be reassessed at a lower level. In comparison an open rating system always adds another, higher grade to its range when an ascent is climbed that is more difficult than has existed thus far. Closed rating systems were used in the early days of mountaineering when it was thought that the complexity of an ascent could not be increased any further. And yet the stormy development of mountaineering overturned this notion, and repeated increase of performance brought the realisation that the boundaries of human ability are inestimable, and to this state an open rating system is better suited.

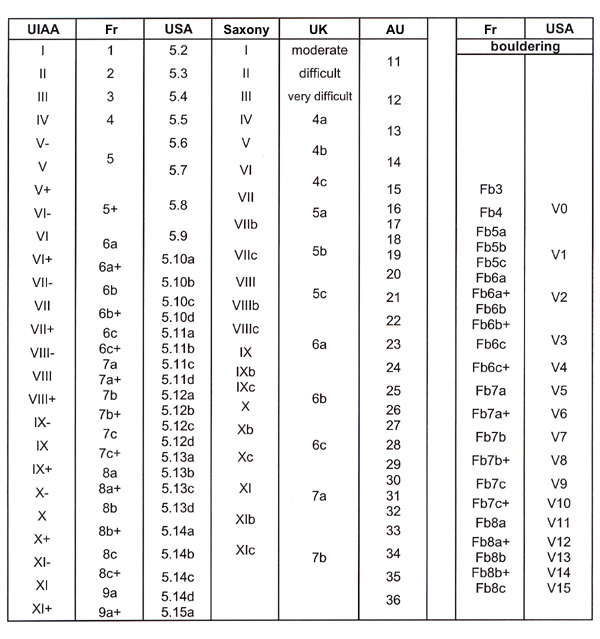

The UIAA international mountaineering organisation attempted to compile a unified standard rating system. While this system is not used exclusively everywhere and while original local systems are retained in some places, “conversion tables” always exist applied primarily to the UIAA rating system. Other propagated methods of classifying ascents are the French, American, Russian, and British rating systems. In the Czech Republic the Saxony rating system is used on sandstone terrain in addition to the UIAA system, while a proprietary rating system is used in the Iser Mountains.

But the territory doesn’t always have to be a decisive criteria for the peculiarity of a rating system. Often rating systems are also part of disciplines (e.g. a bouldering rating system) or according to terrain (a rating system for ice and mixed climbing).

The UIAA rating system is based in structure on the Welzenbach rating system, used particularly in the Alps (named after its founder, the prominent Austrian mountaineer W. Welzenbach).

The Welzenbach rating system had six numerically designated grades starting with the easiest, grade I. Later it followed the Italian model of marking each grade with subgrades using the symbols plus (+) and minus (-), which results in a total of 12 options for differentiating difficulty levels.

The rating system thereby defined was called the Internacionale Alpenskala in the year 1947, and became a direct basis for creation of the UIAA rating system, whose final version was definitively approved in the year 1971.

UIAA rating system

I – Easy. The simplest form of rock climbing, however not terrain only and exclusively for walking. Hands are necessary to ensure balance.

II – Moderately difficult: Beginning climbing, during which the technique of three fixed points is required.

III – Fairly difficult: Intermediate protection recommended on certain exposed places.

IV – Difficult: Climbing experience is essential, sections of this grade usually require more intermediate protection.

V – Very difficult: Climbing now places significant demands on the training of the climber. Often this already involves overhanging sections.

VI – Unusually difficult: Good technique and reliable protection is essential.

VII – Extremely difficult: High exposure often associated with few protection options, even excellent climbers need special preparation for each type of rock in order to climb ascents of this grade without a fall.

VIII through X – Grading of previous complexities, requiring very specific training. Usually this complexity level is inaccessible to climbers who do not train on artificial climbing walls and who do not devote a significant part of their training plan to specific strengthening. Regular climbing at these complexity levels is exclusive to top athletes.

XI – Current boundaries of climbing capability. As a rule, the prior practicing of the route is essential, and not even top climbers are capable of repeating sections at this grade frequently. Ideal conditions, excellent form, and complete concentration on performance are essential for success. This grade of complexity tends to be often completed with previously placed protection.

The UIAA rating system is upwardly open. For more precise differentiation the signs plus (+) and minus (-) are added to the numerical grade, where plus means increased difficulty. According to UIAA principles the ascent should always be described by the author or drawn in a unifying method using topographic marks. The UIAA rating system distinguishes between free climbing, expressed by a rating system, and aid climbing, designated by the grades A0 through A5. The use of expansive pitons (bolts) is designated with the letter “e” (e.g. A4e).

Details of the UIAA classification system: The basic data includes the date of first ascent and the names of the authors, the classification of the hardest climbing spot, a description and diagram of the ascent.

Additional data is composed of information on the character of the terrain (face height, total length of ascent, length of key sections, grade, rock, ice, flowing water, objective danger and retreat options), character of climbing (climbing techniques, quantity of necessary aids, bivouac placement, average time of ascent, data necessary for orientation), and general data (comparison to known ascents in the region, assessment from the perspective of aesthetics).

Rating system for aid climbing

A0 – Piton or other protection is used either as handhold or foothold, basically gripping or stepping on piton.

A1 – Pitons or other protection are easily placed, not much strength is necessary for aid climbing section, the section is relatively short.

A2 – Pitons or other protection are placed with a bit more difficulty, however they hold passably, the section requiring aid climbing is longer.

A3 – Difficult placement of pitons or other protection, which do not hold as well, a longer section.

A4 – Very poor placement of pitons or other protection, necessity of using special pitons or hooks, very difficult.

USA classification system

A very successful classification system is used in the USA. First the basic level (grade) ranging from I to VI expresses the time necessary for the climb (I through III indicates less than one day, IV all day, V up to two days, VI more than two days).

There follow so-called classes ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 through 3 refers to hiking, class 4 designates moderate climbing, and class 5 denotes climbing along steep or vertical rock. Class 5 is considered an open scale, and is subdivided from 1 to the current 15 where from 5.10 on an even finer distinction is achieved through the use of intervals a, b, c, d.

For aid climbing it follows the European model using the designation “A” with five grades. However, unlike Europe the USA uses higher grades to express the danger of a potential fall, for example the grade A5 indicates a fatal fall.

British classification systems

The British system has two parts. The first part captures the complexity (length of ascent, frequency of difficult spots, quality of the rock, etc.). The individual grades are designated using the letters M, D, VD, S, VS, HVS, XS and E, where grade E is further subdivided into sub-grades 1 through the current 10, e.g. E1, E2, etc.

The second part of the British system captures the difficulty of free climbing on the rock. It begins with grade 1, but practical climbing on the rock is captured by grade 4, whereas from this grade on the interval grades a, b, c are used for finer distinction. This system currently goes no higher than 7b.

French classification system

A very popular classification system for rock climbing. It can be used as a documented example of the success of climbers of a specific nationality managing to propagate their given classification throughout the world. Since this rating system is designed only for cliffs, it is fairly simple. It now has seven grades, for finer subdivision from the highest grades the designations of plus (+) and minus (-) are used, while from grade 6 there are further subdivisions a, b, c.

Western Alpine rating system

This classification system is used primarily in the region of the Western Alps (the massif Mont Blanc, Valais Alps, and others).

It has seven grades which express the complexity level of an act performed in the mountain environment. The last highest grade, ABO, is sometimes written in the more detailed grades ED1, ED2, etc.

F Fasile – easy

PD Peu difficile – not very hard

AD Assez difficile – fairly hard

D Difficile – hard

TD Tres difficile – very hard

ED Extremement difficile – extremely hard

ABO Abominable – abominably hard

Russian classification system

The Russian system is very elaborate and detailed, but at the same time it must be said that it is complicated and not as clear. Altogether it can be divided into two parts. The first part (this is very similar to the Western Alp rating system) is called categories and assesses complexity level using six grades, whereas grades 1 through 5 are subdivided into subgrades A and B. This produces the series 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 4A, 4B, 5A, 5B, 6. The second part of the rating system evaluates the difficulty of climbing in rock and ice, and has seven grades, IA, I, II, III, IV, V, VI. Classification of ascent routes is a more complicated process, for which the height above sea level of the terrain is taken into account (the difficulty of grades of rock climbing are corrected accordingly), how much material is needed and how long the ascent lasts.

The Russian difficulty rating system (categories):

1A – Ascents to the summit to a height of 4500 m above sea level, grassy, rubble, or very rugged rock slopes, climbing sections IA, 1-5 metres of section I climbing possible

1B – Rocky, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits at 2000-5000 m height, length of ascent 500 m minimum, ascent is formed on the basis of sections of classification IA, must include 20-30 m sections of grade I climbing or several shorter sections of grade II

2A – Rocky, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits 2000-6000 m in height, length 500 m minimum, the formed on the basis of sections of climbing classification IA and I, must include 5-20 m sections of rock or 80-100 m of snow/ice sections of classification II

2B – Rocky, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits 2000-6000 m high, 500 m length and more, formed on the basis of sections of classification IA and I, must include 15-30 m or longer of rock or a minimum of 80 m ice/snow sections of classification II or 3-3 m of rock or 20-30 m of ice/snow sections of classification III, 1-2 pitons for protection

3A – Rocky, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits 2500-6500 m height, 500-600 m length or more, formed on the basis of sections of classification I and II, must include 10-20 m of rock and 100-200 m of ice/snow sections of classification III, time of ascent 4-6 hours or more, 1-2 pitons for protection

3B – Rock, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits 2500-6500 m high, length 600 m or more, formed on the basis of sections of classification I and II, must include 20-30 m of rock or 200-300 m of ice/snow sections of classification III, 3-8 m of rock or 50-100 m of ice/snow sections of classification IV may appear, time of ascent 5-6 hours or more, 3-8 pitons for protection, traverses must include a minimum of 2 ascents of classification 3A and an unlimited number of ascents of classifications 1 and 2

4A – Rock, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits 2500-7000 m high, length 600 m or more, basis formed by sections of classification II and III, must include 20-50 m of rock or 200-300 m of ice/snow sections of classification IV, time of ascent 6-8 hours or more, 5-20 pitons of protection, traverses must include a minimum of 5 ascents of classification 3A or a minimum of 3 ascents of classification 3B or along with one classification 3B four ascents of classification 3A, or to two ascents of classification or with two ascents of classification 3B a minimum of one classification 3A

4B – Rock, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits with heights 2500-7000 m, length of ascent 600 m or more, basis formed by sections of classification II and III, must include 40-80 m of rocky sections of classification IV, or 3-5 m of classification V, or 300-400 m of ice/snow sections of classification IV, time of ascent 8-10 hours or more, 8-10 pitons for protection, traverses must include a minimum of 2 ascents of classification 4A, of which one may alternate as with 4A (see previous)

5A – Rock, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits 3000-7500 m high, length 600 m or more, basis formed by sections of classification III and IV, must include 10-40 m of rocky or 300-400 m of ice/snow sections of classification V, traverses must include a minimum of 2 ascents of classification 4B and one of 4A, which can alternate in the manner indicated for grade 4A (see above), or unlimited ascents of classification 1-3

5B – Rock, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits 3000-7500 m high, length 700 m or more, basis formed by sections of classification III and IV, must include 50 m of rocky sections of classification V, 2-5 m of sections of classification VI are acceptable, or 600-800 m of ice/snow sections of classification V, sections of classification I and II practically do not occur, time of ascent 15-20 hours or more, 30-50 pitons of protection, traverses must include a minimum of 2 ascents of classification 5A, of which one may alternate in a manner similar to grade 5A (see previous)

6 – Rock, ice/snow, and combined ascents and traverses to summits higher than 3500 m, length of ascent 700-800 m or more, basis formed by sections of classification IV and V, easy and moderately difficult sections practically do not appear, the ascent must include 20 m of sections of classification VI, time of ascent 4050 hours or more, 100-150 pitons for protection, traverses must include a minimum of three ascents of classification 5B, of which one must be sheer

Russia climbing rating system:

IA – very easy – Wide rubble, grass, snow, or rugged rock ridges and slopes 15- 20°, protection not necessary

I – easy – Rubble, ice/snow cliffs 20-30°, not excessively steep rocky sections, it is necessary to use hands, sporadic protection

II – simple – Snow, ice/snow cliffs 25-35°, not to steep rocky sections, for advancement it is necessary to use hands, protection is not necessary

III – moderately difficult – Snow/ice cliffs 35- 45°, steep rock faces, ribs, inside corners, chimneys with good handholds and footholds, or smooth but lying flat, ribs, ridges, protection necessary, descent by rappelling

IV – more than moderately difficult – Steep, rock faces with limited numbers of small handholds and footholds, ice/snow cliffs 45- 55°, very hard to climb with rucksack, descent possible only by rappelling

V – difficult – Steep rocks of various relief with very limited numbers of small handholds and footholds, or a sufficient number of cracks for pitons or other artificial protection, ice of more than 50°, ridges with overhang, climbing with rucksack practically impossible

VI – very difficult – Very difficult vertical or overhanging rocks with significantly limited numbers of handholds and footholds, few cracks for pitons and artificial protection

Classification systems for ice climbing

Most often we can encounter three rating systems:

- original Scottish rating system

- international rating system for ice climbing

- Water Ice (WI) rating system.

Scottish rating system for ice climbing

I Ascent in ice and snow with incline of 45° minimum

II Ascent of ice with incline of 45° minimum with at least a 5 m section at 60° incline

III Ascent with a 45 m section of ice with an incline of 60°, 10 m section with incline of 70° and 2 m section with incline of 90°

IV Ascent with 45 m section of ice with incline of 70°, 15 m section at 80° and 5 m section at 90°

V Ascent with 45 m section of ice with incline of 80° and 20 through 30 m section at 90°

VI Ascent with 45 m section of ice with incline of 90°

International classification system for climbing in ice

This classification system is more appropriate for the assessment of ice ascents in mountain settings. It has two parts.

The first part assesses the complexity and risk of routes using seven grades.

I Short ascent, without objective danger, simple descent.

II Marginal objective danger for a short section of the ascent route, descent can be managed without protection, or only brief rappelling.

III Longer approach, actual ascent route also longer, objective danger on a longer section of the route. Good protection options. Descent by rappelling.

IV Long ascent route with difficult approach under face, objective danger along entire ascent route. Difficult descent.

V Long ascent route, high level of climber required, quality gear. Objective danger great, exposure, avalanche. Very difficult descent.

VI Very long ascent route, on which more than one day is needed. Objective danger great, falls of seracs, rocks, and avalanches. Very difficult descent.

VII Several day climb, significant objective danger, unstable ice. Descent just as horrible as ascent.

The second part of the international rating system for ice climbing assigns difficulty to the actual climbing, this part has nine levels from grade 1 to grade 9.

1 Ascent possible only with crampons

2 Quality ice with one somewhat longer section at 60° incline

3 Mostly quality ice with incline of 70° to 80°, good options for protection in the ice, belay stations in rock

4 Ice of acceptable quality with incline of 75° to 85°, good protection options in the ice

5 Ice of acceptable quality with incline of 85° to 90°, good protection options

6 Ice vertical with occasional moderate icicle overhangs, variable quality of ice and protection

7 Long vertical and overhanging ice (icicles), ice occasionally without adhesion, protection in some places dubious

8 Increased difficulty, ice mostly non-adhesive, protection in rock as well

9 Completely non-adhesive ice in overhangs, frequent break off from the rock, balance climbing, very often protection in the rock

WI classification system for ice climbing difficulty

Another classification system is the WI (Water Ice) system, which is more focused on climbing along ice formations, frozen waterfalls, often even outside of a high altitude mountain setting. The actual WI rating system expresses the difficulty of ice climbing, for higher grades the plus (+) and minus (-) signs are used for finer distinction.

Aside from this the designation “E” is also used, which expresses complexity and objective danger. There are six of these grades from E1 through E6. For E1 this consists of safe recreational ice climbing, for E6 it is a “nightmare” full of risks.

WI1 Ice with incline of 45-60º, ice is compact and of good quality, protection can be placed in almost every spot of the route.

WI2 Ice with incline of 60°-70°, ice is compact and of good quality, protection options are good.

WI3 Ice with incline of 70°-80°, ice is compact, steep passages alternate with rest spots with good options for placing protection.

WI4 Constant ice incline of 80°, small icicles.

WI5 Constant ice incline of 80°, steep passages are longer and with more icicles.

WI5+ Ice incline of 90°, continuous climbing in vertical ice, ice is compact, icicles are firm.

WI6 Continuous climbing in vertical ice, predominantly along fragile and hollow ice and free standing stalactites, thin glacial ice with incline of 80°-85°, climbing along vertical icicles.

WI6+ Continuous climbing in vertical and moderate overhangs of ice, thin and isolated icicles.

WI7 Icefalls, or short and extremely difficult individual passages in overhanging ice and along icicles, often in combination with rock climbing.

WI7+ Overhanging compact ice, very thin free standing and overhanging icicles, this layer of ice in terrain with incline of 85°-90° and icicles in overhanging terrain, climbing often combined with rock climbing.

Classification system for modern mixed climbing

Modern mixed climbing is on the boundary between ice climbing and drytooling. It uses its own specific classification. Individual grades are marked with the letter “M” after which an Arabic letter indicates the value. It is an open classification system, the highest obtainable grade at present is M 14.

Bouldering classification system

After years of development two classification systems were ultimately established, the French Fb system and the American V system. The Fb system (the name is derived from the name of the popular French bouldering region Fontainebleau) more or less copies the French system for rock climbing, except that it is significantly harder. For distinction from common rock climbing systems the abbreviation “Fb” is written before the grade. The American bouldering system is relatively simple, each harder ascent receives a higher grade, designations from V0 to the current V15 are used.