The most common reason for joining two mountaineering ropes is the need for a long rappelling descent. This is particularly the case in mountains, where the mountaineering terrain is of larger dimensions and distances. In the mountains, climbing is also more often performed with two strands of rope (half or double rope), which are used directly for connecting and using longer pitches for rappelling. If a simple rope is usually 50 m, for example, after doubling it up it offers a mere 25 m for rappelling. Meanwhile a two-strand 50 m rope, which we can use in the usual way for rappelling as if it was a simple rope, after joining offers us this very 50 m – twice the length than it would if it was a simple rope. The rope is connected using bend knots. There are many such bend knots. The following list shows the most widely used bend knots, including a description of their characteristics.

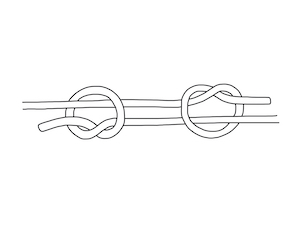

Simple fisherman’s bend

While the simple fisherman’s bend is fully functional, it is not as safe as needed. Only a simple overhand knot on each strand is not enough, with new or thick rope the knot must be pulled completely tight, and could come untied following any unwanted strain, for example rubbing against the rock. For this reason priority is given to the double fisherman’s bend, which can be considered a very safe bend knot.

Double fisherman’s bend

Otherwise also a very good bend for rope of different diameters. The knot is not inclined to untying itself, and therefore it can be applied everywhere that our safety is in question. Of course, on the other hand this knot is rather difficult to untie after heavy tightening, sometimes it takes serious work. It can be a bit of a pain to tie, and people often have difficulty tying it properly, it is particularly unpopular with beginning mountaineers.

And yet it is essential to learn, to gain certainty in tying it and recognising it. Which is important. A complete and tightened double fisherman’s bend may be clear, but a visual check is not enough. Indeed, a fisherman’s bend has a kind of “stepsister” which at first glance seems similar, but in reality is completely different. The error consists of the fact that fisherman’s bends are not tied inward, so as to run into each other, but outward, so that when pulling on the line they pull apart and the rope unties. And to distinguish both knots from one another only by a brief glance is almost impossible. For this reason it is always necessary to examine any fisherman’s bend in detail prior to loading (by feeling the knot, checking how the strands of rope are oriented with a small tug), especially if we are relying on a knot that someone else tied.

More windings of rope in the knot can be carried out than just two, in which case we refer to triple, quadruple, etc. fisherman’s bends. These multiple windings of fisherman’s bends are used at times when the rope is heavily loaded in the place of connection (e.g. on a Tyrolean traverse).

Continued in the book >>